Ancova Can Include One or More Continuous Variables That Predict the Outcome

ANCOVA in R

The Analysis of Covariance (ANCOVA) is used to compare means of an outcome variable between two or more groups taking into account (or to correct for) variability of other variables, called covariates. In other words, ANCOVA allows to compare the adjusted means of two or more independent groups.

For example, you might want to compare "test score" by "level of education" taking into account the "number of hours spent studying". In this example: 1) test score is our outcome (dependent) variable; 2) level of education (high school, college degree or graduate degree) is our grouping variable; 3) sudying time is our covariate.

The one-way ANCOVA can be seen as an extension of the one-way ANOVA that incorporate a covariate variable. The two-way ANCOVA is used to evaluate simultaneously the effect of two independent grouping variables (A and B) on an outcome variable, after adjusting for one or more continuous variables, called covariates.

In this article, you will learn how to:

- Compute and interpret the one-way and the two-way ANCOVA in R

- Check ANCOVA assumptions

- Perform post-hoc tests, multiple pairwise comparisons between groups to identify which groups are different

- Visualize the data using box plots, add ANCOVA and pairwise comparisons p-values to the plot

Contents:

- Assumptions

- Prerequisites

- One-way ANCOVA

- Data preparation

- Check assumptions

- Normality of residuals

- Homogeneity of variances

- Outliers

- Computation

- Post-hoc test

- Report

- Two-way ANCOVA

- Data preparation

- Check assumptions

- Computation

- Post-hoc test

- Report

- Summary

Related Book

Practical Statistics in R II - Comparing Groups: Numerical Variables

Assumptions

ANCOVA makes several assumptions about the data, such as:

- Linearity between the covariate and the outcome variable at each level of the grouping variable. This can be checked by creating a grouped scatter plot of the covariate and the outcome variable.

- Homogeneity of regression slopes. The slopes of the regression lines, formed by the covariate and the outcome variable, should be the same for each group. This assumption evaluates that there is no interaction between the outcome and the covariate. The plotted regression lines by groups should be parallel.

- The outcome variable should be approximately normally distributed. This can be checked using the Shapiro-Wilk test of normality on the model residuals.

- Homoscedasticity or homogeneity of residuals variance for all groups. The residuals are assumed to have a constant variance (homoscedasticity)

- No significant outliers in the groups

Many of these assumptions and potential problems can be checked by analyzing the residual errors. In the situation, where the ANCOVA assumption is not met you can perform robust ANCOVA test using the WRS2 package.

Prerequisites

Make sure you have installed the following R packages:

-

tidyversefor data manipulation and visualization -

ggpubrfor creating easily publication ready plots -

rstatixfor easy pipe-friendly statistical analyses -

broomfor printing a nice summary of statistical tests as data frames -

datarium: contains required data sets for this chapter

Start by loading the following required packages:

library(tidyverse) library(ggpubr) library(rstatix) library(broom) One-way ANCOVA

Data preparation

We'll prepare our demo data from the anxiety dataset available in the datarium package.

Researchers investigated the effect of exercises in reducing the level of anxiety. Therefore, they conducted an experiment, where they measured the anxiety score of three groups of individuals practicing physical exercises at different levels (grp1: low, grp2: moderate and grp3: high).

The anxiety score was measured pre- and 6-months post-exercise training programs. It is expected that any reduction in the anxiety by the exercises programs would also depend on the participant's basal level of anxiety score.

In this analysis we use the pretest anxiety score as the covariate and are interested in possible differences between group with respect to the post-test anxiety scores.

# Load and prepare the data data("anxiety", package = "datarium") anxiety <- anxiety %>% select(id, group, t1, t3) %>% rename(pretest = t1, posttest = t3) anxiety[14, "posttest"] <- 19 # Inspect the data by showing one random row by groups set.seed(123) anxiety %>% sample_n_by(group, size = 1) ## # A tibble: 3 x 4 ## id group pretest posttest ## <fct> <fct> <dbl> <dbl> ## 1 5 grp1 16.5 15.7 ## 2 27 grp2 17.8 16.9 ## 3 37 grp3 17.1 14.3 Check assumptions

Linearity assumption

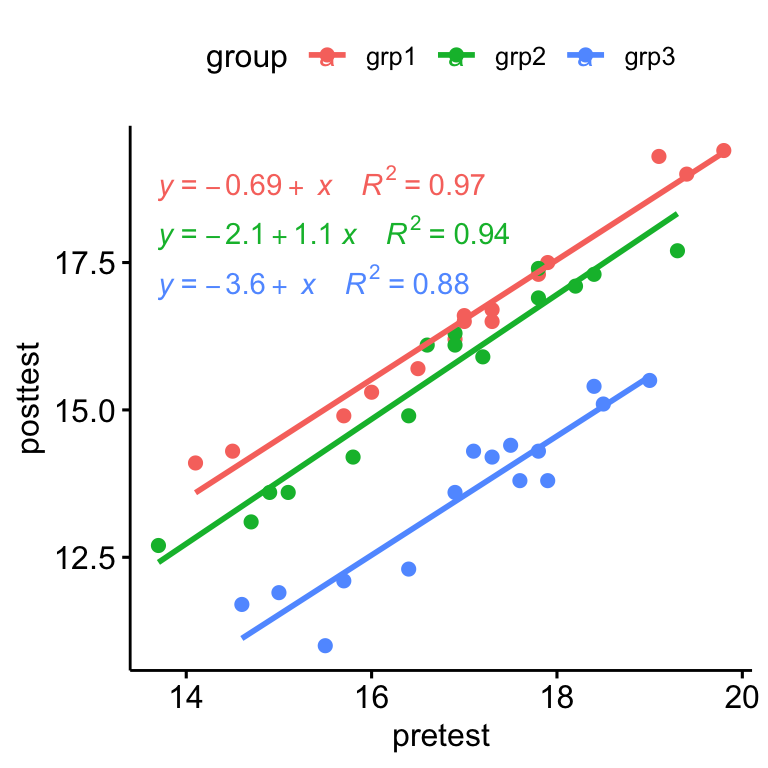

- Create a scatter plot between the covariate (i.e.,

pretest) and the outcome variable (i.e.,posttest) - Add regression lines, show the corresponding equations and the R2 by groups

ggscatter( anxiety, x = "pretest", y = "posttest", color = "group", add = "reg.line" )+ stat_regline_equation( aes(label = paste(..eq.label.., ..rr.label.., sep = "~~~~"), color = group) )

There was a linear relationship between pre-test and post-test anxiety score for each training group, as assessed by visual inspection of a scatter plot.

Homogeneity of regression slopes

This assumption checks that there is no significant interaction between the covariate and the grouping variable. This can be evaluated as follow:

anxiety %>% anova_test(posttest ~ group*pretest) ## ANOVA Table (type II tests) ## ## Effect DFn DFd F p p<.05 ges ## 1 group 2 39 209.314 1.40e-21 * 0.915 ## 2 pretest 1 39 572.828 6.36e-25 * 0.936 ## 3 group:pretest 2 39 0.127 8.81e-01 0.006 There was homogeneity of regression slopes as the interaction term was not statistically significant, F(2, 39) = 0.13, p = 0.88.

Normality of residuals

You first need to compute the model using lm(). In R, you can easily augment your data to add fitted values and residuals by using the function augment(model) [broom package]. Let's call the output model.metrics because it contains several metrics useful for regression diagnostics.

# Fit the model, the covariate goes first model <- lm(posttest ~ pretest + group, data = anxiety) # Inspect the model diagnostic metrics model.metrics <- augment(model) %>% select(-.hat, -.sigma, -.fitted, -.se.fit) # Remove details head(model.metrics, 3) ## # A tibble: 3 x 6 ## posttest pretest group .resid .cooksd .std.resid ## <dbl> <dbl> <fct> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> ## 1 14.1 14.1 grp1 0.550 0.101 1.46 ## 2 14.3 14.5 grp1 0.338 0.0310 0.885 ## 3 14.9 15.7 grp1 -0.295 0.0133 -0.750 # Assess normality of residuals using shapiro wilk test shapiro_test(model.metrics$.resid) ## # A tibble: 1 x 3 ## variable statistic p.value ## <chr> <dbl> <dbl> ## 1 model.metrics$.resid 0.975 0.444 The Shapiro Wilk test was not significant (p > 0.05), so we can assume normality of residuals

Homogeneity of variances

ANCOVA assumes that the variance of the residuals is equal for all groups. This can be checked using the Levene's test:

model.metrics %>% levene_test(.resid ~ group) ## # A tibble: 1 x 4 ## df1 df2 statistic p ## <int> <int> <dbl> <dbl> ## 1 2 42 2.27 0.116 The Levene's test was not significant (p > 0.05), so we can assume homogeneity of the residual variances for all groups.

Outliers

An outlier is a point that has an extreme outcome variable value. The presence of outliers may affect the interpretation of the model.

Outliers can be identified by examining the standardized residual (or studentized residual), which is the residual divided by its estimated standard error. Standardized residuals can be interpreted as the number of standard errors away from the regression line.

Observations whose standardized residuals are greater than 3 in absolute value are possible outliers.

model.metrics %>% filter(abs(.std.resid) > 3) %>% as.data.frame() ## [1] posttest pretest group .resid .cooksd .std.resid ## <0 rows> (or 0-length row.names) There were no outliers in the data, as assessed by no cases with standardized residuals greater than 3 in absolute value.

Computation

The orders of variables matters when computing ANCOVA. You want to remove the effect of the covariate first - that is, you want to control for it - prior to entering your main variable or interest.

The covariate goes first (and there is no interaction)! If you do not do this in order, you will get different results.

res.aov <- anxiety %>% anova_test(posttest ~ pretest + group) get_anova_table(res.aov) ## ANOVA Table (type II tests) ## ## Effect DFn DFd F p p<.05 ges ## 1 pretest 1 41 598 4.48e-26 * 0.936 ## 2 group 2 41 219 1.35e-22 * 0.914 After adjustment for pre-test anxiety score, there was a statistically significant difference in post-test anxiety score between the groups, F(2, 41) = 218.63, p < 0.0001.

Post-hoc test

Pairwise comparisons can be performed to identify which groups are different. The Bonferroni multiple testing correction is applied. This can be easily done using the function emmeans_test() [rstatix package], a wrapper around the emmeans package, which needs to be installed. Emmeans stands for estimated marginal means (aka least square means or adjusted means).

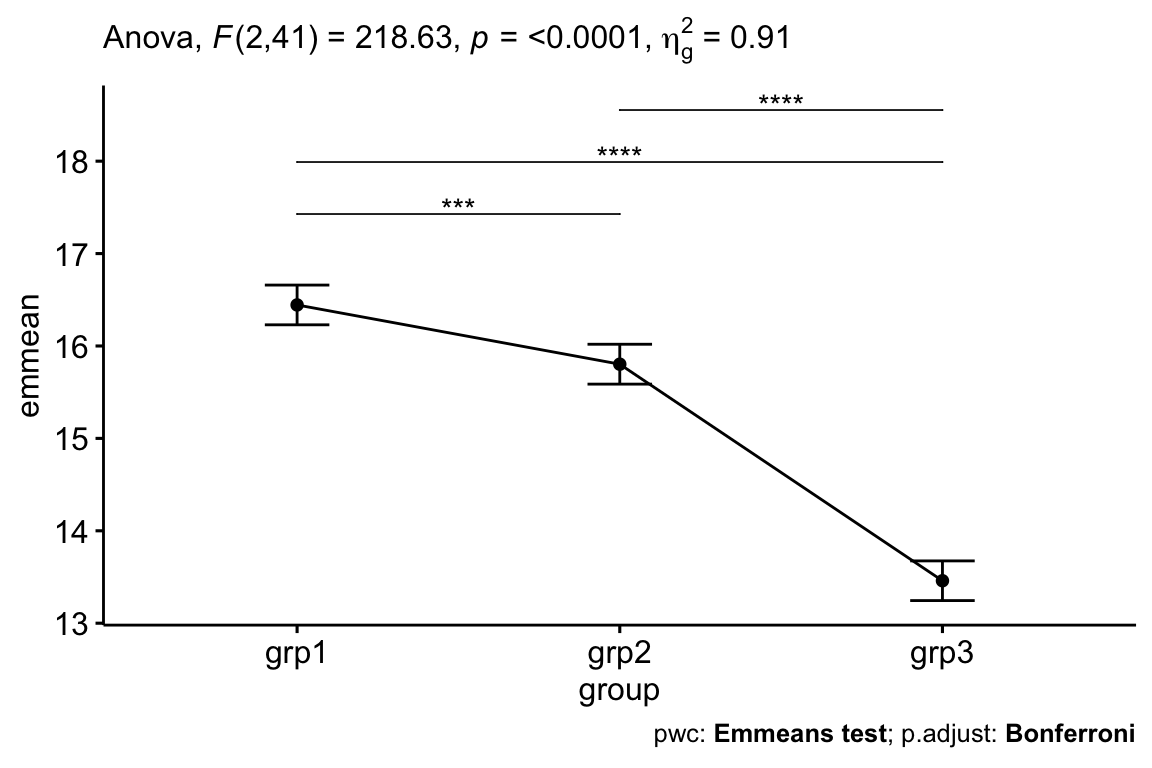

# Pairwise comparisons library(emmeans) pwc <- anxiety %>% emmeans_test( posttest ~ group, covariate = pretest, p.adjust.method = "bonferroni" ) pwc ## # A tibble: 3 x 8 ## .y. group1 group2 df statistic p p.adj p.adj.signif ## * <chr> <chr> <chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <chr> ## 1 posttest grp1 grp2 41 4.24 1.26e- 4 3.77e- 4 *** ## 2 posttest grp1 grp3 41 19.9 1.19e-22 3.58e-22 **** ## 3 posttest grp2 grp3 41 15.5 9.21e-19 2.76e-18 **** # Display the adjusted means of each group # Also called as the estimated marginal means (emmeans) get_emmeans(pwc) ## # A tibble: 3 x 8 ## pretest group emmean se df conf.low conf.high method ## <dbl> <fct> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <chr> ## 1 16.9 grp1 16.4 0.106 41 16.2 16.7 Emmeans test ## 2 16.9 grp2 15.8 0.107 41 15.6 16.0 Emmeans test ## 3 16.9 grp3 13.5 0.106 41 13.2 13.7 Emmeans test Data are adjusted mean +/- standard error. The mean anxiety score was statistically significantly greater in grp1 (16.4 +/- 0.15) compared to the grp2 (15.8 +/- 0.12) and grp3 (13.5 +/_ 0.11), p < 0.001.

Report

An ANCOVA was run to determine the effect of exercises on the anxiety score after controlling for basal anxiety score of participants.

After adjustment for pre-test anxiety score, there was a statistically significant difference in post-test anxiety score between the groups, F(2, 41) = 218.63, p < 0.0001.

Post hoc analysis was performed with a Bonferroni adjustment. The mean anxiety score was statistically significantly greater in grp1 (16.4 +/- 0.15) compared to the grp2 (15.8 +/- 0.12) and grp3 (13.5 +/_ 0.11), p < 0.001.

# Visualization: line plots with p-values pwc <- pwc %>% add_xy_position(x = "group", fun = "mean_se") ggline(get_emmeans(pwc), x = "group", y = "emmean") + geom_errorbar(aes(ymin = conf.low, ymax = conf.high), width = 0.2) + stat_pvalue_manual(pwc, hide.ns = TRUE, tip.length = FALSE) + labs( subtitle = get_test_label(res.aov, detailed = TRUE), caption = get_pwc_label(pwc) )

Two-way ANCOVA

Data preparation

We'll use the stress dataset available in the datarium package. In this study, a researcher wants to evaluate the effect of treatment and exercise on stress reduction score after adjusting for age.

In this example: 1) stress score is our outcome (dependent) variable; 2) treatment (levels: no and yes) and exercise (levels: low, moderate and high intensity training) are our grouping variable; 3) age is our covariate.

Load the data and show some random rows by groups:

data("stress", package = "datarium") stress %>% sample_n_by(treatment, exercise) ## # A tibble: 6 x 5 ## id score treatment exercise age ## <int> <dbl> <fct> <fct> <dbl> ## 1 8 83.8 yes low 61 ## 2 15 86.9 yes moderate 55 ## 3 29 71.5 yes high 55 ## 4 40 92.4 no low 67 ## 5 41 100 no moderate 75 ## 6 56 82.4 no high 53 Check assumptions

Linearity assumption

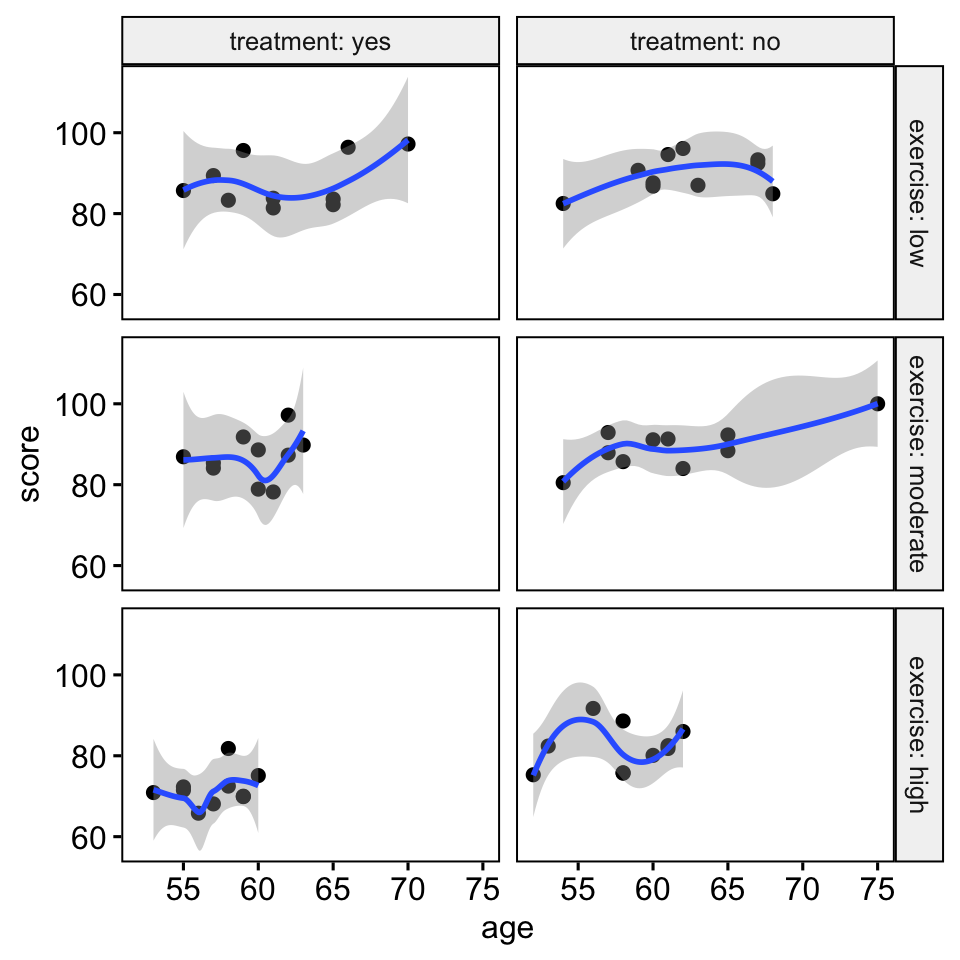

- Create a scatter plot between the covariate (i.e.,

age) and the outcome variable (i.e.,score) for each combination of the groups of the two grouping variables: - Add smoothed loess lines, which helps to decide if the relationship is linear or not

ggscatter( stress, x = "age", y = "score", facet.by = c("exercise", "treatment"), short.panel.labs = FALSE )+ stat_smooth(method = "loess", span = 0.9)

There was a linear relationship between the covariate (age variable) and the outcome variable (score) for each group, as assessed by visual inspection of a scatter plot.

Homogeneity of regression slopes

This assumption checks that there is no significant interaction between the covariate and the grouping variables. This can be evaluated as follow:

stress %>% anova_test( score ~ age + treatment + exercise + treatment*exercise + age*treatment + age*exercise + age*exercise*treatment ) ## ANOVA Table (type II tests) ## ## Effect DFn DFd F p p<.05 ges ## 1 age 1 48 8.359 6.00e-03 * 0.148000 ## 2 treatment 1 48 9.907 3.00e-03 * 0.171000 ## 3 exercise 2 48 18.197 1.31e-06 * 0.431000 ## 4 treatment:exercise 2 48 3.303 4.50e-02 * 0.121000 ## 5 age:treatment 1 48 0.009 9.25e-01 0.000189 ## 6 age:exercise 2 48 0.235 7.91e-01 0.010000 ## 7 age:treatment:exercise 2 48 0.073 9.30e-01 0.003000 Another simple alternative is to create a new grouping variable, say group, based on the combinations of the existing variables, and then compute ANOVA model:

stress %>% unite(col = "group", treatment, exercise) %>% anova_test(score ~ group*age) ## ANOVA Table (type II tests) ## ## Effect DFn DFd F p p<.05 ges ## 1 group 5 48 10.912 4.76e-07 * 0.532 ## 2 age 1 48 8.359 6.00e-03 * 0.148 ## 3 group:age 5 48 0.126 9.86e-01 0.013 There was homogeneity of regression slopes as the interaction terms, between the covariate (age) and grouping variables (treatment and exercise), was not statistically significant, p > 0.05.

Normality of residuals

# Fit the model, the covariate goes first model <- lm(score ~ age + treatment*exercise, data = stress) # Inspect the model diagnostic metrics model.metrics <- augment(model) %>% select(-.hat, -.sigma, -.fitted, -.se.fit) # Remove details head(model.metrics, 3) ## # A tibble: 3 x 7 ## score age treatment exercise .resid .cooksd .std.resid ## <dbl> <dbl> <fct> <fct> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> ## 1 95.6 59 yes low 9.10 0.0647 1.93 ## 2 82.2 65 yes low -7.32 0.0439 -1.56 ## 3 97.2 70 yes low 5.16 0.0401 1.14 # Assess normality of residuals using shapiro wilk test shapiro_test(model.metrics$.resid) ## # A tibble: 1 x 3 ## variable statistic p.value ## <chr> <dbl> <dbl> ## 1 model.metrics$.resid 0.982 0.531 The Shapiro Wilk test was not significant (p > 0.05), so we can assume normality of residuals

Homogeneity of variances

ANCOVA assumes that the variance of the residuals is equal for all groups. This can be checked using the Levene's test:

levene_test(.resid ~ treatment*exercise, data = model.metrics) The Levene's test was not significant (p > 0.05), so we can assume homogeneity of the residual variances for all groups.

Outliers

Observations whose standardized residuals are greater than 3 in absolute value are possible outliers.

model.metrics %>% filter(abs(.std.resid) > 3) %>% as.data.frame() ## [1] score age treatment exercise .resid .cooksd .std.resid ## <0 rows> (or 0-length row.names) There were no outliers in the data, as assessed by no cases with standardized residuals greater than 3 in absolute value.

Computation

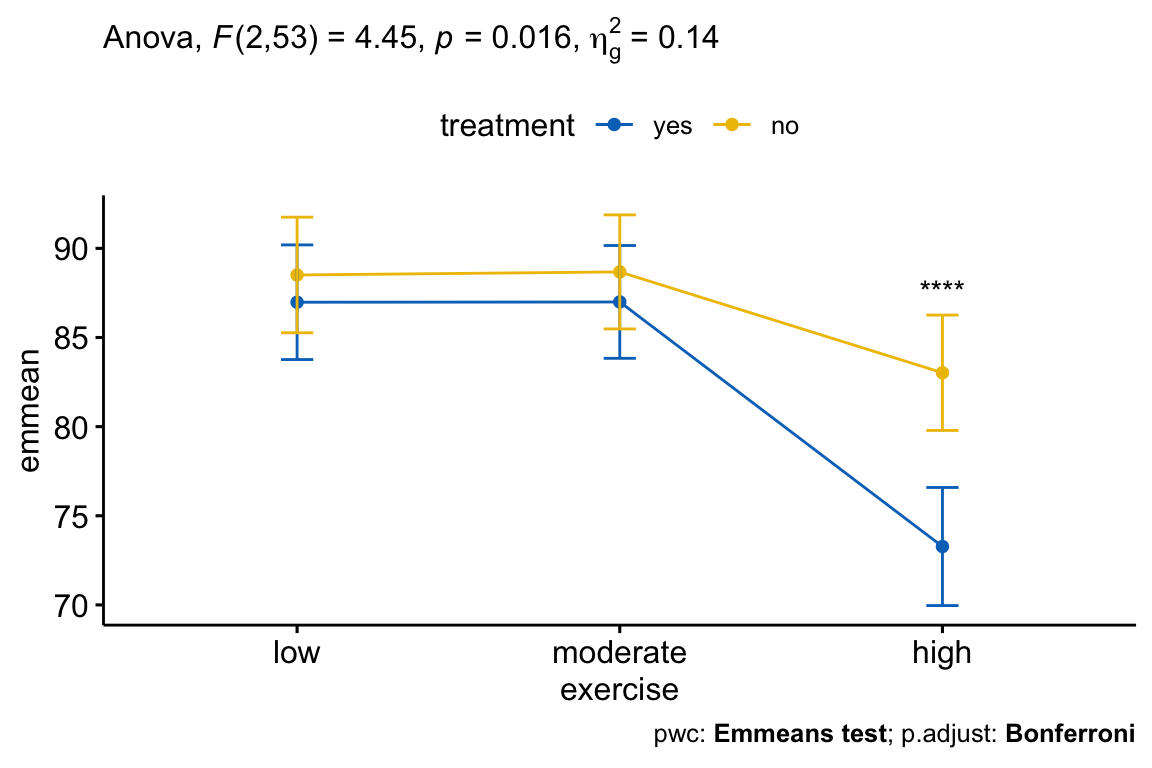

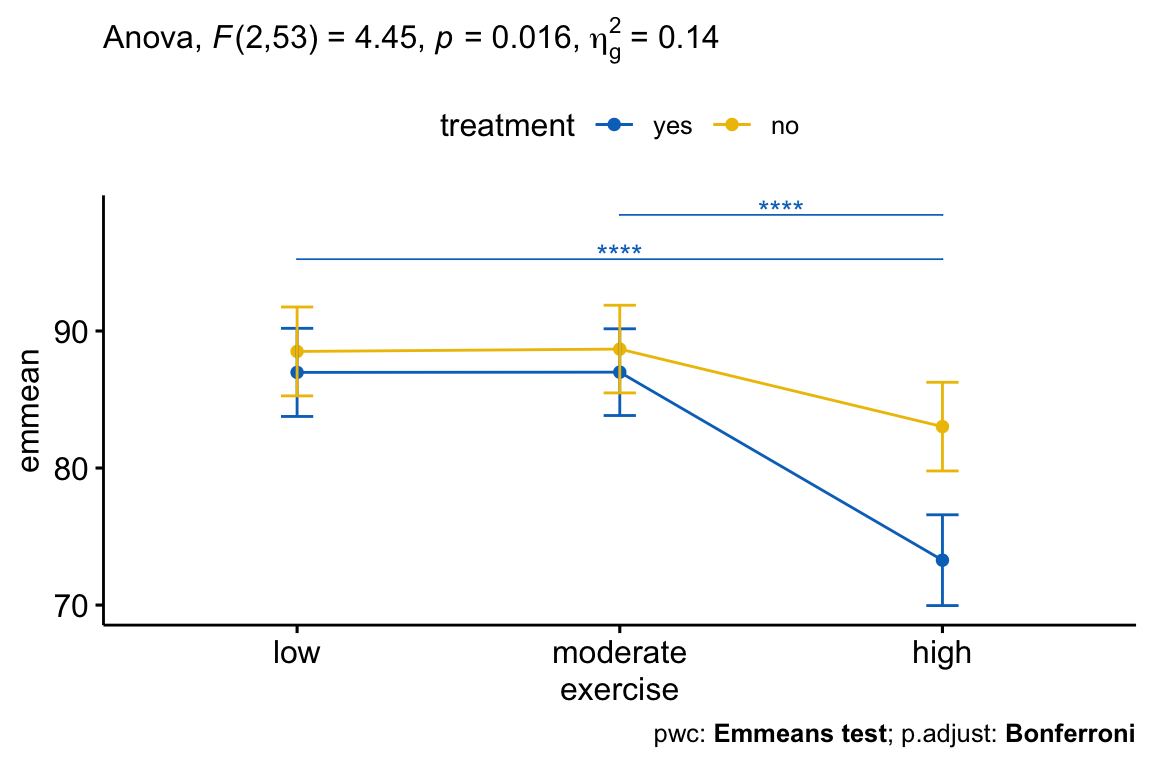

res.aov <- stress %>% anova_test(score ~ age + treatment*exercise) get_anova_table(res.aov) ## ANOVA Table (type II tests) ## ## Effect DFn DFd F p p<.05 ges ## 1 age 1 53 9.11 4.00e-03 * 0.147 ## 2 treatment 1 53 11.10 2.00e-03 * 0.173 ## 3 exercise 2 53 20.82 2.13e-07 * 0.440 ## 4 treatment:exercise 2 53 4.45 1.60e-02 * 0.144 After adjustment for age, there was a statistically significant interaction between treatment and exercise on the stress score, F(2, 53) = 4.45, p = 0.016. This indicates that the effect of exercise on score depends on the level of exercise, and vice-versa.

Post-hoc test

A statistically significant two-way interactions can be followed up by simple main effect analyses, that is evaluating the effect of one variable at each level of the second variable, and vice-versa.

In the situation, where the interaction is not significant, you can report the main effect of each grouping variable.

A significant two-way interaction indicates that the impact that one factor has on the outcome variable depends on the level of the other factor (and vice versa). So, you can decompose a significant two-way interaction into:

- Simple main effect: run one-way model of the first variable (factor A) at each level of the second variable (factor B),

- Simple pairwise comparisons: if the simple main effect is significant, run multiple pairwise comparisons to determine which groups are different.

For a non-significant two-way interaction, you need to determine whether you have any statistically significant main effects from the ANCOVA output.

In this section we'll describe the procedure for a significant three-way interaction

Simple main effect analyses for treatment

Analyze the simple main effect of treatment at each level of exercise. Group the data by exercise and perform one-way ANCOVA for treatment controlling for age:

# Effect of treatment at each level of exercise stress %>% group_by(exercise) %>% anova_test(score ~ age + treatment) ## # A tibble: 6 x 8 ## exercise Effect DFn DFd F p `p<.05` ges ## <fct> <chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <chr> <dbl> ## 1 low age 1 17 2.25 0.152 "" 0.117 ## 2 low treatment 1 17 0.437 0.517 "" 0.025 ## 3 moderate age 1 17 6.65 0.02 * 0.281 ## 4 moderate treatment 1 17 0.419 0.526 "" 0.024 ## 5 high age 1 17 0.794 0.385 "" 0.045 ## 6 high treatment 1 17 18.7 0.000455 * 0.524 Note that, we need to apply Bonferroni adjustment for multiple testing corrections. One common approach is lowering the level at which you declare significance by dividing the alpha value (0.05) by the number of tests performed. In our example, that is 0.05/3 = 0.016667.

Statistical significance was accepted at the Bonferroni-adjusted alpha level of 0.01667, that is 0.05/3. The effect of treatment was statistically significant in the high-intensity exercise group (p = 0.00045), but not in the low-intensity exercise group (p = 0.517) and in the moderate-intensity exercise group (p = 0.526).

Compute pairwise comparisons between treatment groups at each level of exercise. The Bonferroni multiple testing correction is applied.

# Pairwise comparisons pwc <- stress %>% group_by(exercise) %>% emmeans_test( score ~ treatment, covariate = age, p.adjust.method = "bonferroni" ) pwc %>% filter(exercise == "high") ## # A tibble: 1 x 9 ## exercise .y. group1 group2 df statistic p p.adj p.adj.signif ## <fct> <chr> <chr> <chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <chr> ## 1 high score yes no 53 -4.36 0.0000597 0.0000597 **** In the pairwise comparison table, you will only need the result for "exercises:high" group, as this was the only condition where the simple main effect of treatment was statistically significant.

The pairwise comparisons between treatment:no and treatment:yes group was statistically significant in participant undertaking high-intensity exercise (p < 0.0001).

Simple main effect for exercise

You can do the same post-hoc analyses for the exercise variable at each level of treatment variable.

# Effect of exercise at each level of treatment stress %>% group_by(treatment) %>% anova_test(score ~ age + exercise) ## # A tibble: 4 x 8 ## treatment Effect DFn DFd F p `p<.05` ges ## <fct> <chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <chr> <dbl> ## 1 yes age 1 26 2.37 0.136 "" 0.083 ## 2 yes exercise 2 26 17.3 0.0000164 * 0.572 ## 3 no age 1 26 7.26 0.012 * 0.218 ## 4 no exercise 2 26 3.99 0.031 * 0.235 Statistical significance was accepted at the Bonferroni-adjusted alpha level of 0.025, that is 0.05/2 (the number of tests). The effect of exercise was statistically significant in the treatment=yes group (p < 0.0001), but not in the treatment=no group (p = 0.031).

Perform multiple pairwise comparisons between exercise groups at each level of treatment. You don't need to interpret the results for the "no treatment" group, because the effect of exercise was not significant for this group.

pwc2 <- stress %>% group_by(treatment) %>% emmeans_test( score ~ exercise, covariate = age, p.adjust.method = "bonferroni" ) %>% select(-df, -statistic, -p) # Remove details pwc2 %>% filter(treatment == "yes") ## # A tibble: 3 x 6 ## treatment .y. group1 group2 p.adj p.adj.signif ## <fct> <chr> <chr> <chr> <dbl> <chr> ## 1 yes score low moderate 1 ns ## 2 yes score low high 0.00000113 **** ## 3 yes score moderate high 0.000000466 **** There was a statistically significant difference between the adjusted mean of low and high exercise group (p < 0.0001) and, between moderate and high group (p < 0.0001). The difference between the adjusted means of low and moderate was not significant.

Report

A two-way ANCOVA was performed to examine the effects of treatment and exercise on stress reduction, after controlling for age.

There was a statistically significant two-way interaction between treatment and exercise on score concentration, whilst controlling for age, F(2, 53) = 4.45, p = 0.016.

Therefore, an analysis of simple main effects for exercise and treatment was performed with statistical significance receiving a Bonferroni adjustment and being accepted at the p < 0.025 level for exercise and p < 0.0167 for treatment.

The simple main effect of treatment was statistically significant in the high-intensity exercise group (p = 0.00046), but not in the low-intensity exercise group (p = 0.52) and the moderate-intensity exercise group (p = 0.53).

The effect of exercise was statistically significant in the treatment=yes group (p < 0.0001), but not in the treatment=no group (p = 0.031).

All pairwise comparisons were computed for statistically significant simple main effects with reported p-values Bonferroni adjusted. For the treatment=yes group, there was a statistically significant difference between the adjusted mean of low and high exercise group (p < 0.0001) and, between moderate and high group (p < 0.0001). The difference between the adjusted means of low and moderate exercise groups was not significant.

- Create a line plot:

# Line plot lp <- ggline( get_emmeans(pwc), x = "exercise", y = "emmean", color = "treatment", palette = "jco" ) + geom_errorbar( aes(ymin = conf.low, ymax = conf.high, color = treatment), width = 0.1 ) - Add p-values

# Comparisons between treatment group at each exercise level pwc <- pwc %>% add_xy_position(x = "exercise", fun = "mean_se", step.increase = 0.2) pwc.filtered <- pwc %>% filter(exercise == "high") lp + stat_pvalue_manual( pwc.filtered, hide.ns = TRUE, tip.length = 0, bracket.size = 0 ) + labs( subtitle = get_test_label(res.aov, detailed = TRUE), caption = get_pwc_label(pwc) )

# Comparisons between exercises group at each treatment level pwc2 <- pwc2 %>% add_xy_position(x = "exercise", fun = "mean_se") pwc2.filtered <- pwc2 %>% filter(treatment == "yes") lp + stat_pvalue_manual( pwc2.filtered, hide.ns = TRUE, tip.length = 0, step.group.by = "treatment", color = "treatment" ) + labs( subtitle = get_test_label(res.aov, detailed = TRUE), caption = get_pwc_label(pwc2) )

Summary

This article describes how to compute and interpret one-way and two-way ANCOVA in R. We also explain the assumptions made by ANCOVA tests and provide practical examples of R codes to check whether the test assumptions are met or not.

Recommended for you

This section contains best data science and self-development resources to help you on your path.

Version:  Français

Français

Source: https://www.datanovia.com/en/lessons/ancova-in-r/

0 Response to "Ancova Can Include One or More Continuous Variables That Predict the Outcome"

Post a Comment